Asymptotic was started 6 years ago, when I wanted to build something that would be larger than just myself.

We've worked with some incredible clients in this time, on a wide range of projects. I would be remiss to not thank all the teams that put their trust in us.

In addition to working on interesting challenges, our goal was to make sure we were making a positive impact on the open source projects that we are part of. I think we truly punched above our weight class (pardon the boxing metaphor), on this front -- all the upstream work we have done stands testament to that.

Of course, the biggest single contributor to what we were able to achieve is our team. My partner, Deepa, was instrumental in shaping how the company was formed and run. Sanchayan (who took a leap of faith in joining us first), and Taruntej were stellar colleagues and friends on this journey.

It's been an incredibly rewarding experience, but the time has come to move on to other things, and we have now paused operations. I'll soon write about some recent work and what's next.

In my previous post, I alluded to an exciting development for PipeWire. I'm now thrilled to officially announce that Asymptotic will be undertaking several important tasks for the project, thanks to funding from the Sovereign Tech Fund (now part of the Sovereign Tech Agency).

Some of you might be familiar with the Sovereign Tech Fund from their funding for GNOME, GStreamer and systemd – they have been investing in foundational open source technology, supporting the digital commons in key areas, a mission closely aligned with our own.

We will be tackling three key areas of work.

ASHA hearing aid support

I wrote a bit about our efforts on this front. We have already completed the PipeWire support for single ASHA hearing aids, and are actively working on support for stereo pairs.

Improvements to GStreamer elements

We have been working through the GStreamer+PipeWire todo list, fixing bugs and making it easier to build audio and video streaming pipelines on top of PipeWire. A number of usability improvements have already landed, and more work on this front continues

A Rust-based client library

While we have a pretty functional set of Rust bindings around the C-based libpipewire already, we will be creating a pure Rust implementation of a PipeWire client, and provide that via a C API as well.

There are a number of advantages to this: type and memory safety being foremost, but we can also leverage Rust macros to eliminate a lot of boilerplate (there are community efforts in this direction already that we may be able to build upon).

This is a large undertaking, and this funding will allow us to tackle a big chunk of it – we are excited, and deeply appreciative of the work the Sovereign Tech Agency is doing in supporting critical open source infrastructure.

Watch this space for more updates!

It's 2025(!), and I thought I'd kick off the year with a post about some work

that we've been doing behind the scenes for a while. Grab a cup of

$beverage_of_choice, and let's jump in with some context.

History: Hearing aids and Bluetooth

Various estimates put the number of people with some form of hearing loss at 5% of the population. Hearing aids and cochlear implants are commonly used to help deal with this (I'll use "hearing aid" or "HA" in this post, but the same ideas apply to both). Historically, these have been standalone devices, with some primitive ways to receive audio remotely (hearing loops and telecoils).

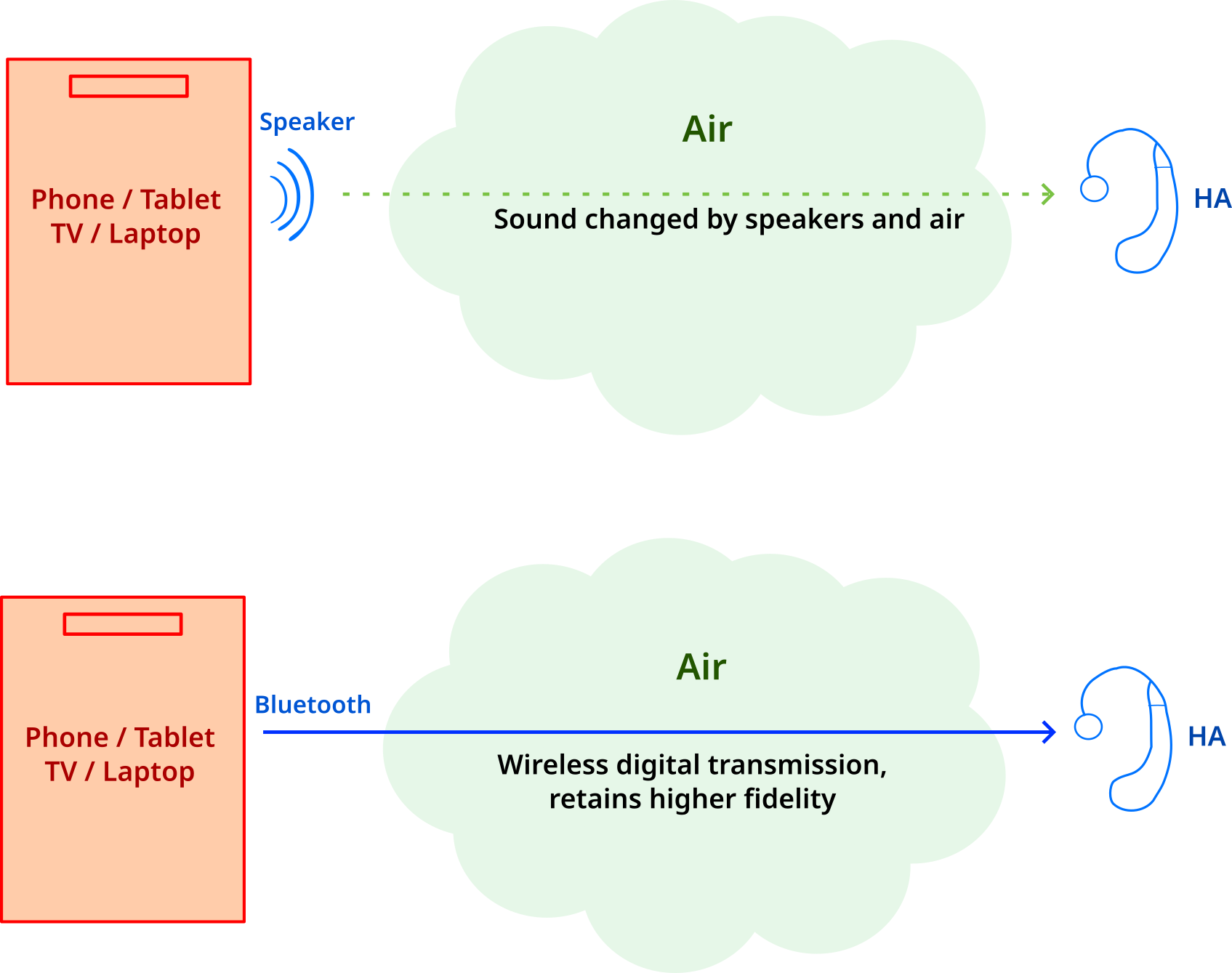

As you might expect, the last couple of decades have seen advances that allow consumer devices (such as phones, tablets, laptops, and TVs) to directly connect to hearing aids over Bluetooth. This can provide significant quality of life improvements -- playing audio from a device's speakers means the sound is first distorted by the speakers, and then by the air between the speaker and the hearing aid. Avoiding those two steps can make a big difference in the quality of sound that reaches the user.

Unfortunately, the previous Bluetooth audio standards (BR/EDR and A2DP -- used by most Bluetooth audio devices you've come across) were not well-suited for these use-cases, especially from a power-consumption perspective. This meant that HA users would either have to rely on devices using proprietary protocols (usually limited to Apple devices), or have a cumbersome additional dongle with its own battery and charging needs.

Recent Past: Bluetooth LE

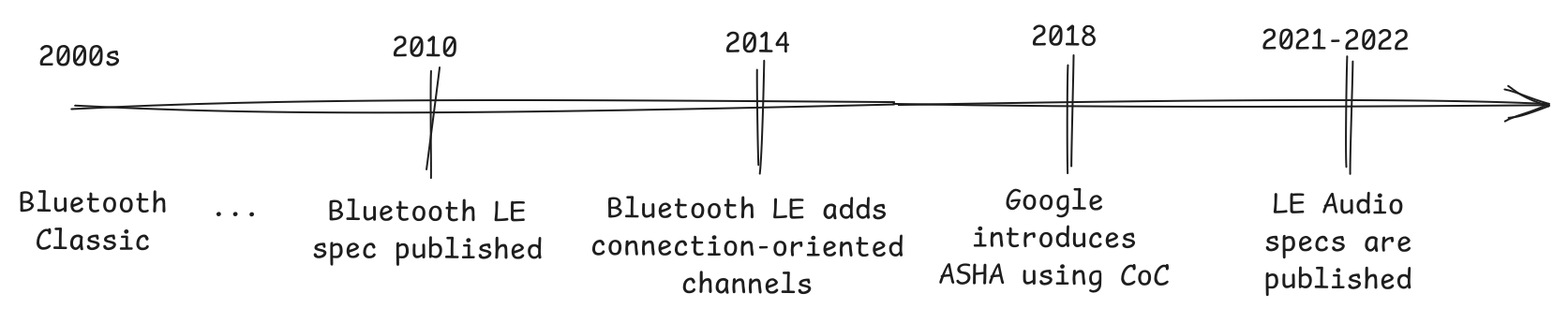

The more recent Bluetooth LE specification addresses some of the issues with the previous spec (now known as Bluetooth Classic). It provides a low-power base for devices to communicate with each other, and has been widely adopted in consumer devices.

On top of this, we have the LE Audio standard, which provides audio streaming services over Bluetooth LE for consumer audio devices and HAs. The hearing aid industry has been an active participant in its development, and we should see widespread support over time, I expect.

The base Bluetooth LE specification has been around from 2010, but the LE Audio specification has only been public since 2021/2022. We're still seeing devices with LE Audio support trickle into the market.

In 2018, Google partnered with a hearing aid manufacturer to announce the ASHA (Audio Streaming for Hearing Aids) protocol, presumably as a stop-gap. The protocol uses Bluetooth LE (but not LE Audio) to support low-power audio streaming to hearing aids, and is publicly available. Several devices have shipped with ASHA support in the last ~6 years.

Hot Take: Obsolescence is bad UX

As end-users, we understand the push/pull of technological advancement and obsolescence. As responsible citizens of the world, we also understand the environmental impact of this.

The problem is much worse when we are talking about medical devices. Hearing aids are expensive, and are expected to last a long time. It's not uncommon for people to use the same device for 5-10 years, or even longer.

In addition to the financial cost, there is also a significant emotional cost to changing devices. There is usually a period of adjustment during which one might be working with an audiologist to tune the device to one's hearing. Neuroplasticity allows the brain to adapt to the device and extract more meaning over time. Changing devices effectively resets the process.

All this is to say that supporting older devices is a worthy goal in itself, but has an additional set of dimensions in the context of accessibility.

HAs and Linux-based devices

Because of all this history, hearing aid manufacturers have traditionally focused on mobile devices (i.e. Android and iOS). This is changing, with Apple supporting its proprietary MFi (made for iPhone/iPad/iPod) protocol on macOS, and Windows adding support for LE Audio on Windows 11.

This does leave the question of Linux-based devices, which is our primary concern -- can users of free software platforms also have an accessible user experience?

A lot of work has gone into adding Bluetooth LE support in the Linux kernel and BlueZ, and more still to add LE Audio support. PipeWire's Bluetooth module now includes support for LE Audio, and there is continuing effort to flesh this out. Linux users with LE Audio-based hearing aids will be able to take advantage of all this.

However, the ASHA specification was only ever supported on Android devices. This is a bit of a shame, as there are likely a significant number of hearing aids out there with ASHA support, which will hopefully still be around for the next 5+ years. This felt like a gap that we could help fill.

Step 1: A Proof-of-Concept

We started out by looking at the ASHA specification, and the state of Bluetooth LE in the Linux kernel. We spotted some things that the Android stack exposes that BlueZ does not, but it seemed like all the pieces should be there.

Friend-of-Asymptotic, Ravi Chandra Padmala spent some time with us to implement a proof-of-concept. This was a pretty intense journey in itself, as we had to identify some good reference hardware (we found an ASHA implementation on the onsemi RSL10), and clean out the pipes between the kernel and userspace (LE connection-oriented channels, which ASHA relies on, weren't commonly used at that time).

We did eventually get the proof-of-concept done, and this gave us confidence to move to the next step of integrating this into BlueZ -- albeit after a hiatus of paid work. We have to keep the lights on, after all!

Step 2: ASHA in BlueZ

The BlueZ audio plugin implements various audio profiles within the BlueZ daemon -- this includes A2DP for Bluetooth Classic, as well as BAP for LE Audio.

We decided to add ASHA support within this plugin. This would allow BlueZ to perform privileged operations and then hand off a file descriptor for the connection-oriented channel, so that any userspace application (such as PipeWire) could actually stream audio to the hearing aid.

I implemented an initial version of the ASHA profile in the BlueZ audio plugin last year, and thanks to Luiz Augusto von Dentz' guidance and reviews, the plugin has landed upstream.

This has been tested with a single hearing aid, and stereo support is pending.

In the process, we also found a small community of folks with deep interest in

this subject, and you can join us on #asha on the

BlueZ Slack.

Step 3: PipeWire support

To get end-to-end audio streaming working with any application, we need to expose the BlueZ ASHA profile as a playback device on the audio server (i.e., PipeWire). This would make the HAs appear as just another audio output, and we could route any or all system audio to it.

My colleague, Sanchayan Maity, has been working on this for the last few weeks. The code is all more or less in place now, and you can track our progress on the PipeWire MR.

Step 4 and beyond: Testing, stereo support, ...

Once we have the basic PipeWire support in place, we will implement stereo support (the spec does not support more than 2 channels), and then we'll have a bunch of testing and feedback to work with. The goal is to make this a solid and reliable solution for folks on Linux-based devices with hearing aids.

Once that is done, there are a number of UI-related tasks that would be nice to have in order to provide a good user experience. This includes things like combining the left and right HAs to present them as a single device, and access to any tuning parameters.

Getting it done

This project has been on my mind since the ASHA specification was announced, and it has been a long road to get here. We are in the enviable position of being paid to work on challenging problems, and we often contribute our work upstream. However, there are many such projects that would be valuable to society, but don't necessarily have a clear source of funding.

In this case, we found ourselves in an interesting position -- we have the expertise and context around the Linux audio stack to get this done. Our business model allows us the luxury of taking bites out of problems like this, and we're happy to be able to do so.

However, it helps immensely when we do have funding to take on this work end-to-end -- we can focus on the task entirely and get it done faster.

Onward...

I am delighted to announce that we were able to find the financial support to complete the PipeWire work! Once we land basic mono audio support in the MR above, we'll move on to implementing stereo support in the BlueZ plugin and the PipeWire module. We'll also be testing with some real-world devices, and we'll be leaning on our community for more feedback.

This is an exciting development, and I'll be writing more about it in a follow-up post in a few days. Stay tuned!

I wrote about our time at the GStreamer Conference in October, and one important thing I was able to do is spend some time with all-around great guy George reflecting on where the GStreamer plugins for PipeWire are, and what we need to do to get them to a rock-solid state.

This is a summary of our conversation, in the form of a to-do list of sorts...

Status Quo

Currently, we have two elements: pipewiresrc and pipewiresink. The two plugins work with both audio and video, and instantiate a PipeWire capture and playback stream, respectively. The stream, as with any PipeWire client, appears as a node in the PipeWire.

Buffers are managed in the GStreamer pipeline using bufferpools, and recently Wim re-enabled exposing the stream clock as a GStreamer clock.

There have been a number of issues that have cropped up over time, and we've been plugging away at addressing them, but it was worth stepping back and looking at the whole for a bit.

Use Cases

The straightforward uses of these elements might be to represent client streams: pipewiresrc might connect to an audio capture device (like a microphone), or video capture device (like a webcam), and provide the data for downstream elements to consume. Similarly pipewiresink might be used to play audio to the system output (speakers or headphones, perhaps).

Because of the flexibility of the PipeWire API, these elements may also be used to provide a virtual capture or playback device though. So pipewiresrc might provide a virtual audio sink, which applications could connect to to stream audio over the network (like say a WebRTC stream).

Conversely, it is possible to use pipewiresink to provide a virtual capture device -- for example, the pipeline might generate a video stream and expose it a virtual camera for other applications to use.

We might even combine the two cases, one might connect to a webcam as a client, apply some custom video processing, and then expose that stream back as a virtual camera source as easily as:

pipewiresrc target-object="MyCamera" ! <some video filters> ! \

pipewiresink provide=true stream-properties="props,media.class=Video/Source,media.role=Camera"

So we have a minor combinatorial explosion across 3 axes, and all combinations are valid:

pipewiresrcvs.pipewiresink- audio vs. video

- stream vs. virtual device

For each of these combinations, we might have different behaviour across the various issues below.

Split 'em up?

Before we look at specific issues, it is worth pointing out that the PipeWire elements are unusual in that they support both audio and video with the same code. This seems like a tantalisingly elegant idea, and it's quite neat that we are able to get this far with this unified approach.

However, as we examine the specific issues we are seeing, it does seem to emerge that the audio and video paths diverge in several ways. It may be time to consider whether the divergence merits just splitting them up into separate audio and video elements.

Linking

The first issue that comes to mind is how we might want PipeWire or WirePlumber to manage linking the nodes from the GStreamer pipeline with other nodes (devices or streams).

For the playback/capture stream use-cases, we would want the nodes to automatically be connected to a sink/source node when the GStreamer pipeline goes to the PAUSED or PLAYING state, and for that link to be torn down when leaving those states. It might be possible for the link to "move" if, for example, the default playback or capture device changes, though a "move" is really the removal of the current link with a new link following.

For the virtual device use-cases, the pipeline state should likely follow the link state. That is, when a node is connected to our virtual device, we want the GStreamer pipeline to start producing/consuming data, and when disconnected, it should go back to "sleep", possibly running again later.

The latter is something that a GStreamer application using these plugins might have to manage manually, but simplifying this and supporting this via gst-launch-1.0 for easy command-line use would be nice to have.

There are already the beginnings of support for such usage via the provide property on pipewiresink, but more work is needed for this to make this truly usable.

Bufferpools

Closely related to linking are buffers and bufferpools, as the process of linking nodes is what makes buffers for data exchange available to PipeWire nodes.

While bufferpools are a valuable concept for memory efficiency and avoiding unnecessary memcpy()s, they come with some complexity overhead in managing the pipeline. For one, as the number of buffers in a bufferpool is limited, it is possible to exhaust the set of buffers (with a large queue for example).

There are also some lifecycle complexities that arise from links coming and going, as the corresponding buffers also then go away from under us, something that GStreamer bufferpools are not designed for.

A solution to the first problem might be to avoid using bufferpools for some cases (for example, they might not be very valuable for audio). The solution to the lifecycle problem is a trickier one, and no clear answer is apparent yet, at least with the APIs as they stand.

We might also need to support resizing bufferpools for some cases, and that is not something that is easy to support with how buffer management currently happens in PipeWire (the stream API does not really give us much of a handle on this).

Formats

In order to support the various use-cases, we want to be able to support both a fixed format (if we know what we are providing), or a negotiated format (if we can adapt in the GStreamer pipeline based on what PipeWire has/wants).

There is also a large surface area of formats that PipeWire supports that we need to make sure we support well:

- There are known issues with some planar video formats being presented correctly from

pipewiresrc - We do not expose planar audio formats, although both GStreamer and PipeWire support them

- Support for DSD and passthrough audio (e.g. Dolby/DTS over HDMI) needs to be wired up

- Support for compressed formats (we added PipeWire support for decode + render on a DSP)

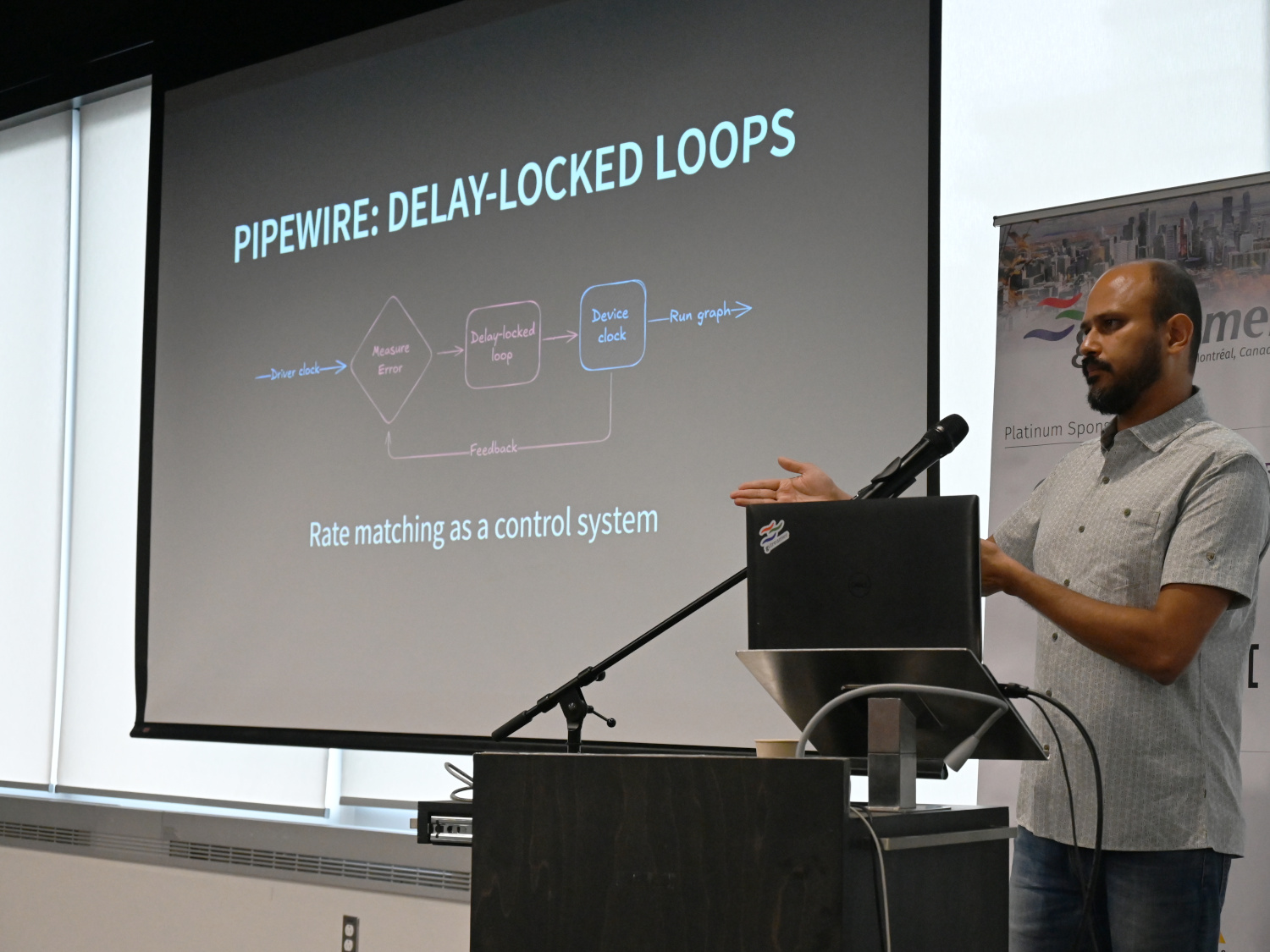

Rate matching

While Wim recently added some rate matching code to pipewiresink, there is work to be done to make sure that if there is skew between the GStreamer pipeline's data rate and the audio device rate, we can use PipeWire's rate adaptation features to compensate for such skew. This should work in both pipewiresink and pipewiresrc.

For some background on this topic, check out my talk on clock rate matching from a couple of months ago.

Device provider conflicts

While we are improving the out-of-the-box experience of these elements, unfortunately the PipeWire device provider currently supersedes all others (the GStreamer Device Provider API allows for discovering devices on the system and the elements used to access them).

The higher rank might make sense for video (as system integrators likely want to start preferring PipeWire elements over V4L2), but it can lead to a bad experience for audio (the PulseAudio elements work better today via PipeWire's PulseAudio emulation layer).

We might temporarily drop the rank of PipeWire elements for audio to avoid autoplugging them while we fix the problems we have.

Probing formats

We create a "probe" stream in pipewiresink while getting ready to play audio, in order to discover what formats the device we would play to supports. This is required to detect supported formats and make decisions about whether to decode in GStreamer, what sample rate and format are preferred, etc.

Unfortunately, that also causes a "false" playback device startup sequence, which might manifest as a click or glitch on some hardware. Having a way to set up a probe that does not actually open the device would be a nice improvement.

Player state

There are a couple of areas where policy actions do not always surface well to the application/UI layer. One instance of this is where a stream is "corked" (maybe because only one media player should be active at a time) -- we want to let the player know it has been paused, so it can update its state and let the UI know too. There is limited infrastructure for this already, via GST_MESSAGE_REQUEST_STATE.

Also, more of a session management (i.e. WirePlumber / system integration) thing, we do not really have the concept of a system-wide media player state. This would be useful if we want to exercise policy like "don't let any media player play while we're on a call", and have that state be consistent across UI interactions (i.e. hitting play during a call does not trigger playback, maybe even lets the user know why it's not working / provides an override).

All of us at Asymptotic are back home from the exciting week at GStreamer Conference 2024 in Montréal, Canada last month. It was great to hang out with the community and see all the great work going on in the GStreamer ecosystem.

There were some visa-related adventures leading up to the conference, but thanks to the organising team (shoutout to Mark Filion and Tim-Philipp Müller), everything was sorted out in time and Sanchayan and Taruntej were able to make it.

This conference was also special because this year marks the 25th anniversary of the GStreamer project!

Talks

We had 4 talks at the conference this year.

GStreamer & QUIC (video)

Sanchayan spoke about his work with the various QUIC elements in GStreamer. We

already have the quinnquicsrc and quinquicsink upstream, with a couple of

plugins to allow (de)multiplexing of raw streams as well as an implementation

or RTP-over-QUIC (RoQ). We've also started work on Media-over-QUIC (MoQ)

elements.

This has been a fun challenge for us, as we're looking to build out a general-purpose toolkit for building QUIC application-layer protocols in GStreamer. Watch this space for more updates as we build out more functionality, especially around MoQ.

Clock Rate Matching in GStreamer & PipeWire (video)

My talk was about an interesting corner of GStreamer, namely clock rate matching. This is a part of live pipelines that is often taken for granted, so I wanted to give folks a peek under the hood.

The idea of doing this talk was was born out of some recent work we did to allow splitting up the graph clock in PipeWire from the PTP clock when sending AES67 streams on the network. I found the contrast between the PipeWire and GStreamer approaches thought-provoking, and wanted to share that with the community.

GStreamer for Real-Time Audio on Windows (video)

Next, Taruntej dove into how we optimised our usage of GStreamer in a real-time audio application on Windows. We had some pretty tight performance requirements for this project, and Taruntej spent a lot of time profiling and tuning the pipeline to meet them. He shared some of the lessons learned and the tools he used to get there.

Simplifying HLS playlist generation in GStreamer (video)

Sanchayan also walked us through the work he's been doing to simplify HLS multivariant playlist generation. This should be a nice feature to round out GStreamer's already strong support for generating HLS streams. We are also exploring the possibility of reusing the same code for generating DASH manifests.

Hackfest

As usual, the conference was followed by a two-day hackfest. We worked on a few interesting problems:

-

Sanchayan addressed some feedback on the QUIC muxer elements, and then investigated extending the HLS elements for SCTE-35 marker insertion and DASH support

-

Taruntej worked on improvements to the

threadshareelements, specifically to bring somets-udpsrcelement features in line withudpsrc -

I spent some time reviewing a long-pending merge request to add soft-seeking support to the AWS S3 sink (so that it might be possible to upload seekable MP4s, for example, directly to S3). I also had a very productive conversation with George Kiagiadakis about how we should improve the PipeWire GStreamer elements (more on this soon!)

All in all, it was a great time, and I'm looking forward to the spring hackfest and conference in the the latter part next year!

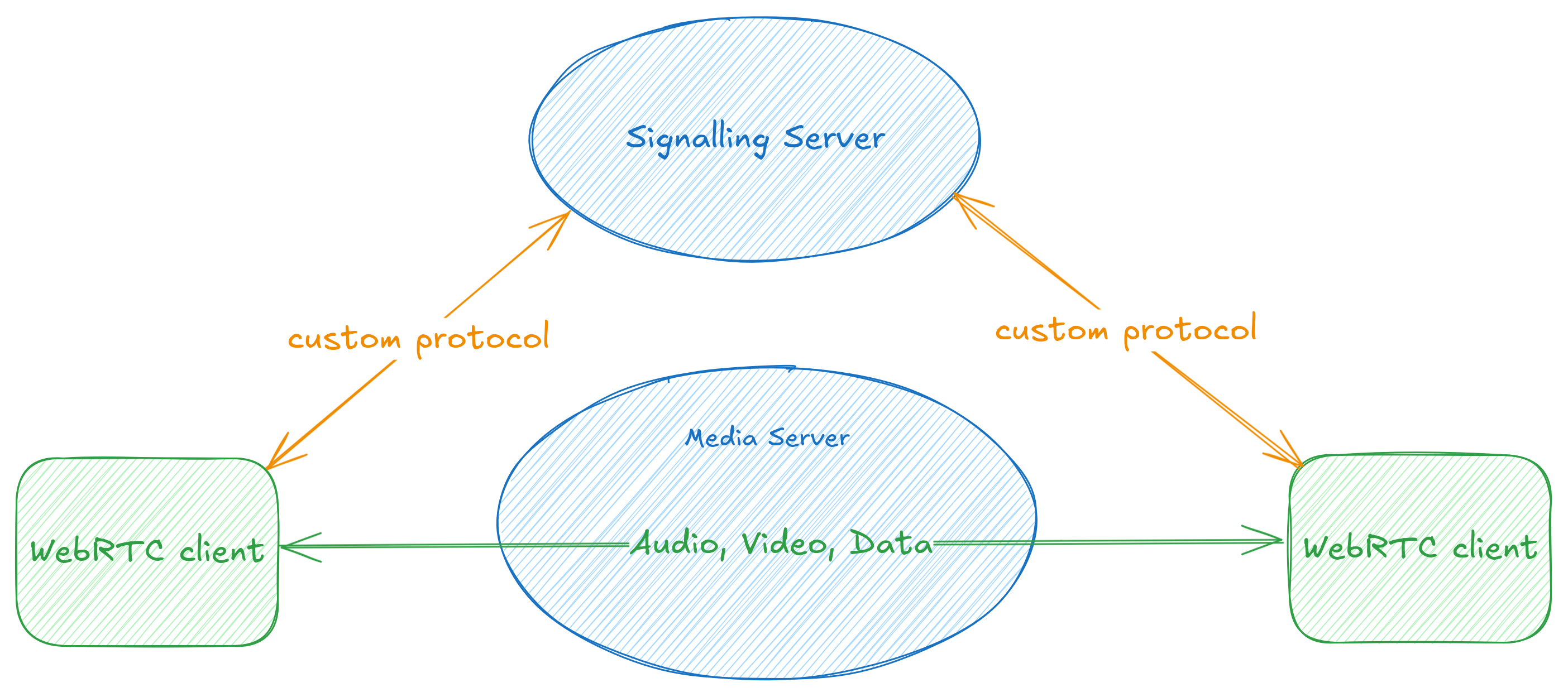

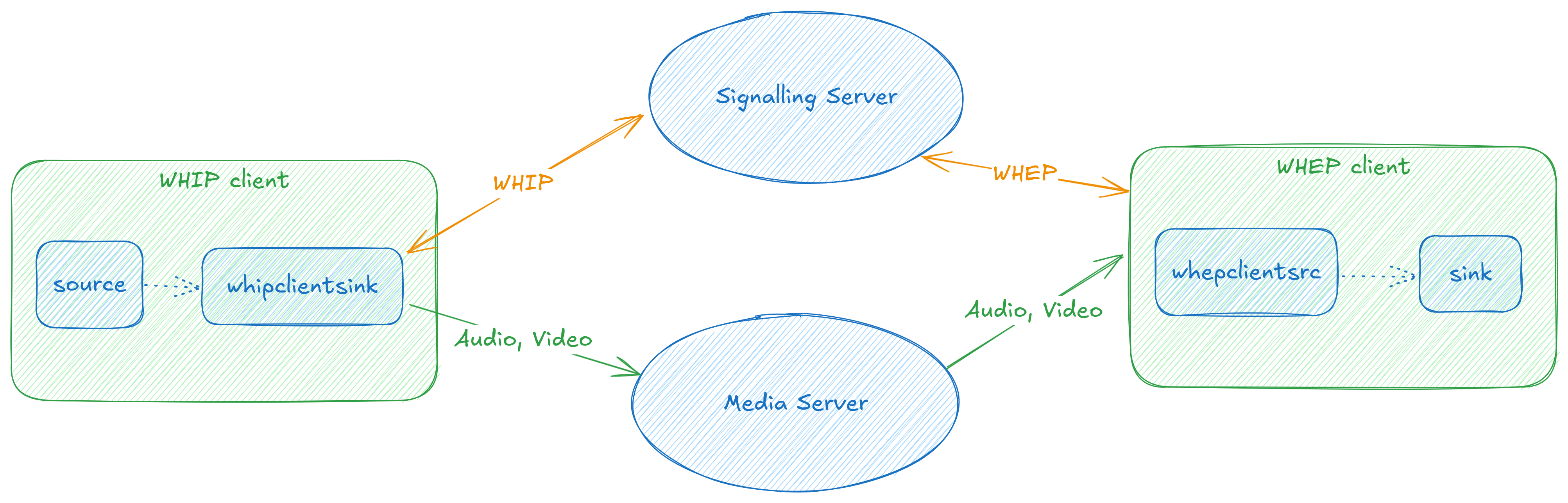

The WebRTC nerds among us will remember the first thing we learn about WebRTC, which is that it is a specification for peer-to-peer communication of media and data, but it does not specify how signalling is done.

Or put more simply, if you want call someone on the web, WebRTC tells you how you can transfer audio, video and data, but it leaves out the bit about how you make the call itself: how do you locate the person you're calling, let them know you'd like to call them, and a few following steps before you can see and talk to each other.

While this allows services to provide their own mechanisms to manage how WebRTC

calls work, the lack of a standard mechanism means that general-purpose

applications need to individually integrate each service that they want to

support. For example, GStreamer's webrtcsrc and webrtcsink elements support

various signalling protocols, including Janus Video Rooms, LiveKit, and Amazon

Kinesis Video Streams.

However, having a standard way for clients to do signalling would help developers focus on their application and worry less about interoperability with different services.

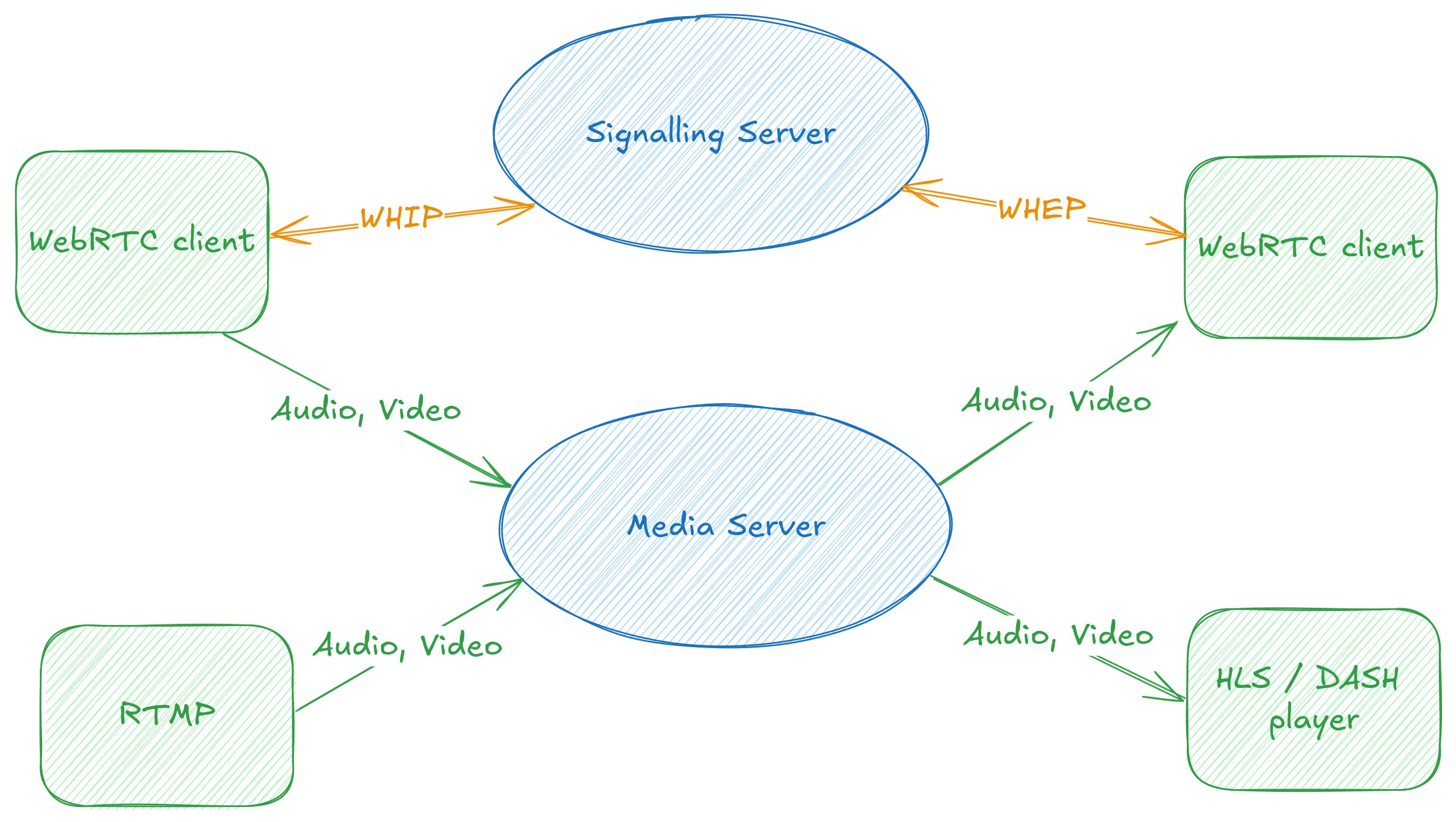

Standardising Signalling

With this motivation, the IETF WebRTC Ingest Signalling over HTTPS (WISH) workgroup has been working on two specifications:

- WebRTC-HTTP Ingestion protocol (WHIP)

- WebRTC-HTTP Egress Protocol (WHEP)

(author's note: the puns really do write themselves :))

As the names suggest, the specifications provide a way to perform signalling using HTTP. WHIP gives us a way to send media to a server, to ingest into a WebRTC call or live stream, for example.

Conversely, WHEP gives us a way for a client to use HTTP signalling to consume a WebRTC stream -- for example to create a simple web-based consumer of a WebRTC call, or tap into a live streaming pipeline.

With this view of the world, WHIP and WHEP can be used both for calling applications, but also as an alternative way to ingest or play back live streams, with lower latency and a near-ubiquitous real-time communication API.

In fact, several services already support this including Dolby Millicast, LiveKit and Cloudflare Stream.

WHIP and WHEP with GStreamer

We know GStreamer already provides developers two ways to work with WebRTC streams:

-

webrtcbin: provides a low-level API, akin to thePeerConnectionAPI that browser-based users of WebRTC will be familiar with -

webrtcsrcandwebrtcsink: provide high-level elements that can respectively produce/consume media from/to a WebRTC endpoint

At Asymptotic, my colleagues Tarun and Sanchayan have been using these building blocks to implement GStreamer elements for both the WHIP and WHEP specifications. You can find these in the GStreamer Rust plugins repository.

Our initial implementations were based on webrtcbin, but have since been

moved over to the higher-level APIs to reuse common functionality (such as

automatic encoding/decoding and congestion control). Tarun covered our work in

a talk at last year's GStreamer Conference.

Today, we have 4 elements implementing WHIP and WHEP.

Clients

-

whipclientsink: This is awebrtcsink-based implementation of a WHIP client, using which you can send media to a WHIP server. For example, streaming your camera to a WHIP server is as simple as:gst-launch-1.0 -e \ v4l2src ! video/x-raw ! queue ! \ whipclientsink signaller::whip-endpoint="https://my.webrtc/whip/room1" -

whepclientsrc: This is work in progress and allows us to build player applications to connect to a WHEP server and consume media from it. The goal is to make playing a WHEP stream as simple as:gst-launch-1.0 -e \ whepclientsrc signaller:whep-endpoint="https://my.webrtc/whep/room1" ! \ decodebin ! autovideosink

The client elements fit quite neatly into how we might imagine GStreamer-based clients could work. You could stream arbitrary stored or live media to a WHIP server, and play back any media a WHEP server provides. Both pipelines implicitly benefit from GStreamer's ability to use hardware-acceleration capabilities of the platform they are running on.

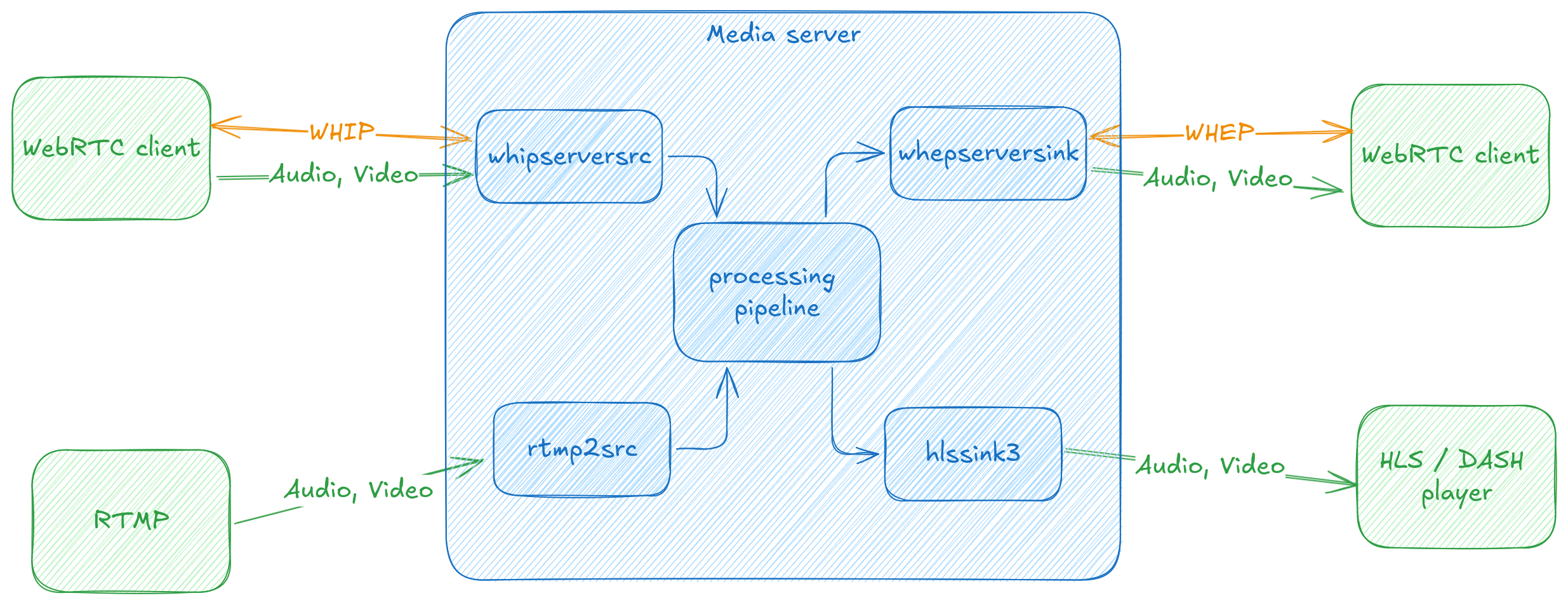

Servers

-

whipserversrc: Allows us to create a WHIP server to which clients can connect and provide media, each of which will be exposed as GStreamer pads that can be arbitrarily routed and combined as required. We have an example server that can play all the streams being sent to it. -

whepserversink: Finally we have ongoing work to publish arbitrary streams over WHEP for web-based clients to consume this media.

The two server elements open up a number of interesting possibilities. We can ingest arbitrary media with WHIP, and then decode and process, or forward it, depending on what the application requires. We expect that the server API will grow over time, based on the different kinds of use-cases we wish to support.

This is all pretty exciting, as we have all the pieces to create flexible pipelines for routing media between WebRTC-based endpoints without having to worry about service-specific signalling.

If you're looking for help realising WHIP/WHEP based endpoints, or other media streaming pipelines, don't hesitate to reach out to us!

Some time has passed since the GStreamer spring hackfest took place in Thessaloniki, Greece in the month of May. Second time attending the GStreamer hackfest and thought about summarizing some of my thoughts this time around.

Thanks

Before getting into the details, want to send out a thank you to:

- The GStreamer foundation for sponsoring the event as a whole

- Sebastian, Vivia and Jordan for making all the arrangements

- Asymptotic, for sponsoring my presence at the event

The event

It was good to see some familiar faces at the event, folks whom I had met at the previous hackfest and conference. Also nice when you finally meet people you have only conversed with online and get to put a face on the online persona you have been conversing with.

Work

Originally the plan was to work on adding stream multiplexing support to QUIC elements. However, missed pushing some of the work to GitLab which was on desktop and decided to work on that later.

HTTP Live Streaming (HLS)

A merge request for adding multi-variant playlist support with HLS has been pending review for a while. One of the features missing from that merge request was support for codec string generation when using MPEG-TS with H.264 and H.265. Decided to work on that.

H.264 or H.265 has what are known as stream-formats. H.264 or H.265 can be stream oriented or packet oriented. In the case of former, stream-format is said to be byte-stream, while in the case of latter, stream-format is said to be avc. For byte-stream, the required parameter sets are sent in-band with the video, but for avc in GStreamer, the video metadata is conveyed via an additional caps field named codec_data which can be considered as out-of-band. codec_data is only present when the video is packet oriented, that's when stream-format is avc, this value represents an AVCDecoderConfigurationRecord structure.

GStreamer already has helper functions in codec utilities which can provide information like profile-level which are required for constructing codec strings. However, these helper functions require the existence of codec_data.

When using MPEG-TS as the container, the only possible stream-format is byte-stream with H.264 or H.265. In this case, one needs to parse the in-band information for getting information like profile-level or other video metadata. In Rust, there is the cros-codecs crate which has a parser module. Using this, it was easy to parse the in-band data and then generate the codec string required for HLS playlist.

Threadshare

Before the hackfest, had spend some time on understanding the threadshare elements. Met François Laignel at the hackfest who helped with clearing doubts I had with how some of the code was laid out in threadshare.

If you are interested in understanding about what makes the threadshare elements different, highly recommend going through the blog post here.

There was some end-of-stream handling missing with the threadshare, tcpclientsrc and udpsrc elements. Spend some time working on adding support for that, which has now been merged upstream.

Play

After the three days of hackfest, a day trip was planned to the Palace of Aigai.

GStreamer hackers & co. exploring the Palace of Aigai.

Conclusion

All in all, this hackfest turned out to be a productive and fun filled hackfest. Also, have to add that Greek cuisine is excellent and look forward to the next hackfest and visiting Thessaloniki/Greece again.

Motivation

When using headphones or in-ear monitors (IEMs), one might want to EQ their headphones or IEMs. Equalization or EQ is the process of adjusting the volume of different frequency bands in an audio signal. Some popular EQ software are EasyEffects on Linux and Equalizer APO on Windows. PipeWire supports EQ via the filter-chain module.

For an understanding of EQ, following resources might help.

- The Headphone Show - EQ Basics

- The Headphone Show - The Limits of EQ

- Graphs 101 - How to Read Headphone Measurements

The basic idea is that there are some “standard” frequency response curves that might sound good to different individuals, and knowing the frequency response characteristics of a specific headphone/IEM model, you can apply a set of filters via an equalizer to achieve something close to the “standard” frequency response curve that sounds good to you.

Websites like Squig or autoeq.app generate a file for parametric equalization for a given target, but this isn't a format that can be directly given to filter chain module. Squig is also useful for evaluating the frequency response curves of various in-ear monitors and headphones when making buying decisions.

An example of Parametric EQ generated from either AutoEQ or Squig looks like below.

Preamp: -6.8 dB

Filter 1: ON PK Fc 20 Hz Gain -1.3 dB Q 2.000

Filter 2: ON PK Fc 31 Hz Gain -7.0 dB Q 0.500

Filter 3: ON PK Fc 36 Hz Gain 0.7 dB Q 2.000

Filter 4: ON PK Fc 88 Hz Gain -0.4 dB Q 2.000

Fc is the frequency, Gain is the amount with which the signal gets boosted or attenuated around that frequency. Q factor controls the bandwidth around the frequency point. To be more precise, Q is the ratio of center frequency to bandwidth. If the center frequency is fixed, the bandwidth is inversely proportional to Q implying that as one raises the Q, the bandwidth is narrowed. Q is by far the most useful tool a parametric EQ offers, allowing one to attenuate or boost a narrow or wide range of frequencies within each EQ band.

If one wants to build a better intuition for this, playing around with the filter type and parameters here, and seeing the effects on the frequency response helps. This linked article also goes into the basics of filters.

EasyEffects allows importing such a file via it’s Import APO option, however, one might want to use an EQ input like this directly in PipeWire without having to resort to additional software like EasyEffects. However, during the course of testing, trying out multiple EQ is definitely much easier with EasyEffects GUI.

Now, this needs to be converted manually into something which filter-chain module can accept.

To simplify this, a simple PipeWire module is implemented which reads a parametric EQ text file like preceding and loads filter chain module while translating the inputs from the text file to what the filter chain module expects.

It's been a busy few several months, but now that we have some breathing

room, I wanted to take stock of what we have done over the last year or so.

This is a good thing for most people and companies to do of course, but being a scrappy, (questionably) young organisation, it's doubly important for us to introspect. This allows us to both recognise our achievements and ensure that we are accomplishing what we have set out to do.

One thing that is clear to me is that we have been lagging in writing about some of the interesting things that we have had the opportunity to work on, so you can expect to see some more posts expanding on what you find below, as well as some of the newer work that we have begun.

(note: I write about our open source contributions below, but needless to say, none of it is possible without the collaboration, input, and reviews of members of the community)

WHIP/WHEP client and server for GStreamer

If you're in the WebRTC world, you likely have not missed the excitement around standardisation of HTTP-based signalling protocols, culminating in the WHIP and WHEP specifications.

Tarun has been driving our client and server

implementations for both these protocols, and in the process has been

refactoring some of the webrtcsink and webrtcsrc code to make it easier to

add more signaller implementations. You can find out more about this work in

his talk at GstConf 2023

and we'll be writing more about the ongoing effort here as well.

Low-latency embedded audio with PipeWire

Some of our work involves implementing a framework for very low-latency audio processing on an embedded device. PipeWire is a good fit for this sort of application, but we have had to implement a couple of features to make it work.

It turns out that doing timer-based scheduling can be more CPU intensive than ALSA period interrupts at low latencies, so we implemented an IRQ-based scheduling mode for PipeWire. This is now used by default when a pro-audio profile is selected for an ALSA device.

In addition to this, we also implemented rate adaptation for USB gadget devices using the USB Audio Class "feedback control" mechanism. This allows USB gadget devices to adapt their playback/capture rates to the graph's rate without having to perform resampling on the device, saving valuable CPU and latency.

There is likely still some room to optimise things, so expect to more hear on this front soon.

Compress offload in PipeWire

Sanchayan has written about the work we did to add support in PipeWire for offloading compressed audio. This is something we explored in PulseAudio (there's even an implementation out there), but it's a testament to the PipeWire design that we were able to get this done without any protocol changes.

This should be useful in various embedded devices that have both the hardware and firmware to make use of this power-saving feature.

GStreamer LC3 encoder and decoder

Tarun wrote a GStreamer plugin implementing the LC3 codec

using the liblc3 library. This is the

primary codec for next-generation wireless audio devices implementing the

Bluetooth LE Audio specification. The plugin is upstream and can be used to

encode and decode LC3 data already, but will likely be more useful when the

existing Bluetooth plugins to talk to Bluetooth devices get LE audio support.

QUIC plugins for GStreamer

Sanchayan implemented a QUIC source and sink plugin in Rust, allowing us to start experimenting with the next generation of network transports. For the curious, the plugins sit on top of the Quinn implementation of the QUIC protocol.

There is a merge request open that should land soon, and we're already seeing folks using these plugins.

AWS S3 plugins

We've been fleshing out the AWS S3 plugins over the years, and we've added a

new awss3putobjectsink. This provides a better way to push small or sparse

data to S3 (subtitles, for example), without potentially losing data in

case of a pipeline crash.

We'll also be expecting this to look a little more like multifilesink,

allowing us to arbitrary split up data and write to S3 directly as multiple

objects.

Update to webrtc-audio-processing

We also updated the webrtc-audio-processing

library, based on more recent upstream libwebrtc. This is one of those things

that becomes surprisingly hard as you get into it -- packaging an API-unstable

library correctly, while supporting a plethora of operating system and

architecture combinations.

Clients

We can't always speak publicly of the work we are doing with our clients, but there have been a few interesting developments we can (and have spoken about).

Both Sanchayan and I spoke a bit about our work with WebRTC-as-a-service provider, Daily. My talk at the GStreamer Conference was a summary of the work I wrote about previously about what we learned while building Daily's live streaming, recording, and other backend services. There were other clients we worked with during the year with similar experiences.

Sanchayan spoke about the interesting approach to building SIP support that we took for Daily. This was a pretty fun project, allowing us to build a modern server-side SIP client with GStreamer and SIP.js.

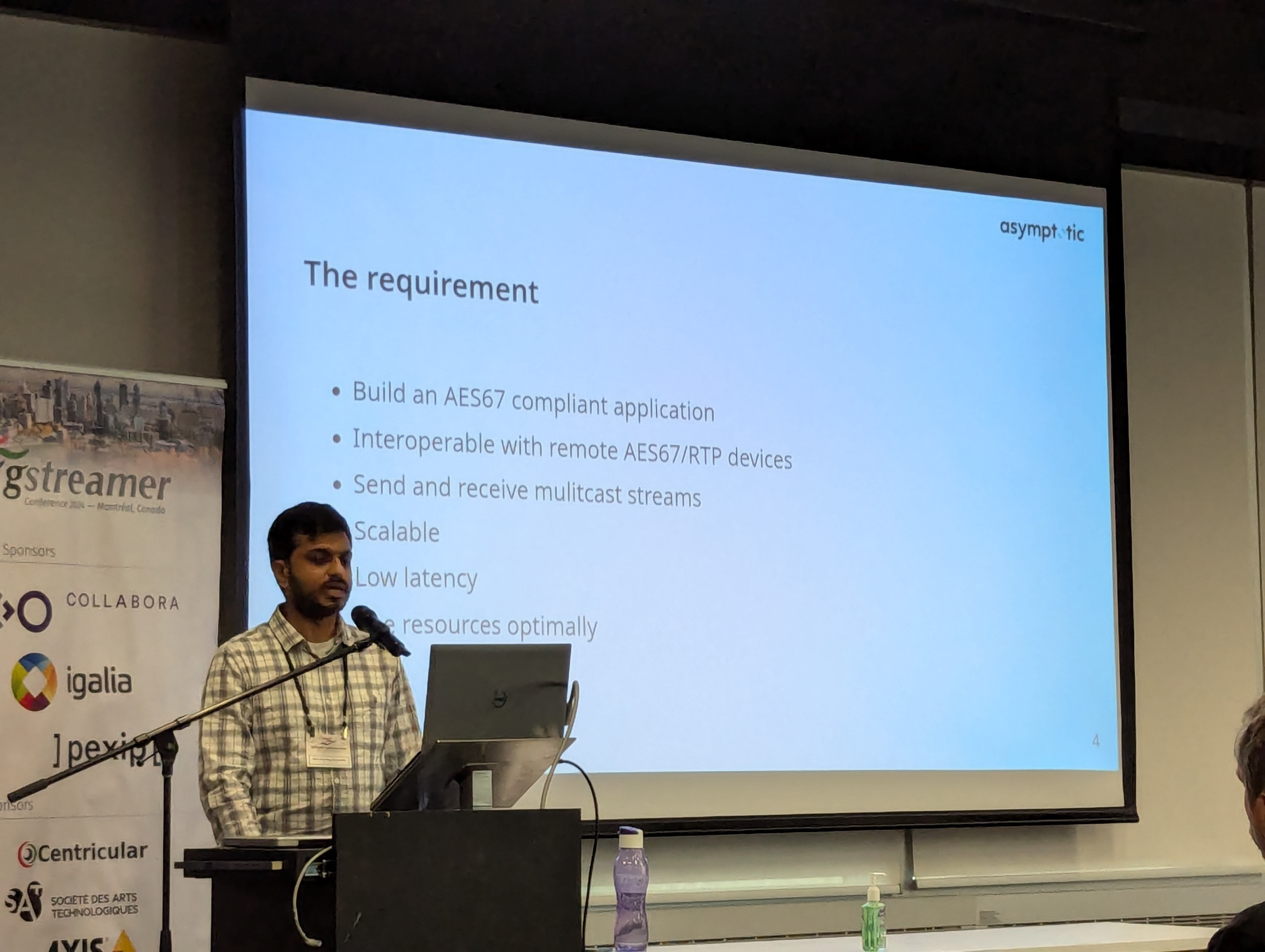

An ongoing project we are working on is building AES67 support using GStreamer for FreeSWITCH, which essentially allows bridging low-latency network audio equipment with existing SIP and related infrastructure.

As you might have noticed from previous sections, we are also working on a low-latency audio appliance using PipeWire.

Retrospective

All in all, we've had a reasonably productive 2023. There are things I know we can do better in our upstream efforts to help move merge requests and issues, and I hope to address this in 2024.

We have ideas for larger projects that we would like to take on. Some of these we might be able to find clients who would be willing to pay for. For the ideas that we think are useful but may not find any funding, we will continue to spend our spare time to push forward.

If you made this this far, thank you, and look out for more updates!

Editor's note: this work was completed in late 2022 but this post was unfortunately delayed.

Modern day audio hardware these days comes integrated with Digital Signal Processors integrated in SoCs and audio codecs. Processing compressed or encoded data in such DSPs results in power savings in comparison to carrying out such processing on the CPU.

+---------+ +---------+ +---------+

| CPU | ---> | DSP | ---> | Codec |

| | <--- | | <--- | |

+---------+ +---------+ +---------+

This post takes a look at how all this works.

For the last year and a half, we at Asymptotic have been working with the excellent team at Daily. I'd like to share a little bit about what we've learned.

Daily is a real time calling platform as a service. One standard feature that users have come to expect in their calls is the ability to record them, or to stream their conversations to a larger audience. This involves mixing together all the audio/video from each participant and then storing it, or streaming it live via YouTube, Twitch, or any other third-party service.

As you might expect, GStreamer is a good fit for building this kind of functionality, where we consume a bunch of RTP streams, composite/mix them, and then send them out to one or more external services (Amazon's S3 for recordings and HLS, or a third-party RTMP server).

I've written about how we implemented this feature elsewhere, but I'll summarise briefly.

This is a slightly longer post than usual, so grab a cup of your favourite beverage, or jump straight to the summary section for the tl;dr.

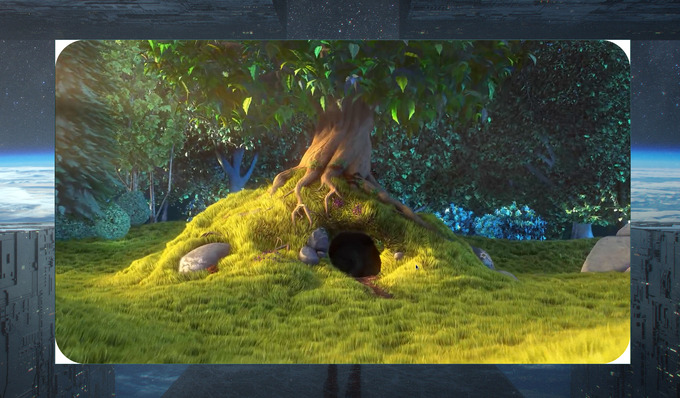

Recently I was working on a GStreamer

plugin

in Rust. The plugin basically rounds the corners of an incoming video,

something akin to the border-radius property in CSS. Below is how it looks

like when running on a video.

The GStreamer pipeline for the same:

gst-launch-1.0 filesrc location=~/Downloads/bunny.mp4 ! \

decodebin ! videoconvert ! \

roundedcorners border-radius-px=100 ! \

videoconvert ! gtksink

This was my first time working on a video plugin in GStreamer. Had a lot to

learn on how to use the BaseTransform class from GStreamer, among other

things. Without getting into the GStreamer specific details here, I basically

ran into a problem for which I needed to do some debugging for figuring out

what was going on in the internals of GStreamer.

Now, while I never had problems using GDB from the command line, but, the way I was using it earlier was just not good enough. I would start the pipeline, then attach gdb to a running process, place breakpoints by manually typing out the whole thing and then start. For one off debugging sessions, where may be you just want to quickly inspect the backtrace from a crash or may be look into a deadlock condition where your code hung, this could be fine. However, when you have to repeat this multiple times, do a source code change, compile and then check again, it becomes frustrating.

Let's look at how we can make this easier.

It's 2021, and while many things have changed for the better, they haven't changed enough, particularly in technology.

Right from the get-go, we knew we wanted to build a diverse company. Our founding team was balanced in gender terms. Our next hire was someone intimately familiar with the world we inhabited, and whom we knew through a Rust meetup that he organised.

We are determined to ensure that our hiring pipeline reflects the world we live in (rather than the world we work in). We've had a broad set of people vet our hiring page to ensure that the language is inclusive, and welcoming. We've reached out to folks we know and asked them to help us reach under-represented members in tech.

These are baby steps. We will continue doing our very best to build an inclusive, and welcoming space for everyone. We're acutely aware that gender is not the only axis of representation, and this is something we hope to address over time as well.

Here are some of the policies we've adopted to further our aim of building a diverse, and inclusive space. As we grow (slowly and sustainably), our intention is to continue to put progressive and employee-friendly policies in place.

Remote work

Offices are often designed around male-centric preferences. From the ergonomics of the workstation, to the temperature of the room, or the typical work schedule, professional spaces rarely account for differing priorities or perspectives. Remote work allows for more diverse participation.

Working hours

A full working week for us is 35 hours. We want to allow you the flexibility of scheduling your work day in a way that's most comfortable to you, while allowing for reasonable overlap with your team. We don't work weekends.

Conferences

We encourage and support both speaking at, and attending conferences, all over the world.

Paid menstrual leave

Taking nilenso's lead, we have adopted a no questions asked paid menstrual leave policy.

Paid leave

We currently operate with a flexible ("as needed") paid leave policy. We encourage people to regularly take time off. As we grow, we will likely introduce a more formal policy.

We started asymptotic 2½ years ago, and have been fortunate to have had a wild and busy ride so far. Nevertheless, it's probably high time we introduced ourselves! :-)

We are a small team of people who care about software freedom and take pride in their craft. Being tinkerers, we like working on low-level systems and are happiest when we're close to the metal.

We contribute to open source projects upstream, and help companies use them in products that are useful to people in the real world. This allows us to produce a virtuous cycle of improving the projects we maintain, while ensuring that they solve real world problems.

We want to live in a world where open source software is the default choice, and we aim to achieve that by making the projects we work on be the best option available.

Together, we're building a diverse, inclusive and sustainable company. This may mean choosing to be slow and deliberate while we grow. We're fine with that, because we believe that is the right path for us to achieve our goals while upholding the values we care about.

If you would like to join us on our journey, or would like to talk to us, please reach out!